I was flattered and surprised to be asked by UNA-UK’s Chair, Lord Wood, to serve as Guest Editor for this issue of the UNA-UK magazine. I agreed because I felt that the story this magazine will tell – the story of the United Nations’ relationship with the Syrian conflict – is a very important one.

Of course, any conflict in which some 400,000 people have died, five million refugees have been created and 13.5 million people are in desperate need of humanitarian assistance deserves thorough analysis. But the crisis in Syria also holds lessons for how the UN responds to crises, and it is important that these lessons are learned, both to bring the suffering in Syria to an end and to empower the UN to prevent, manage and resolve conflict in the future.

Yes, the UN failed to stop the bloodshed in Syria, but a deeper understanding is needed of why the UN fails when it fails, and why the UN succeeds when it succeeds.

The UN is no more than the sum of its parts, its member states, and can do no more than what those members – especially the most powerful ones – will allow it to do. The UN remains an indispensable institution, but one that only has a limited number of tools at its disposal to prevent conflict. In the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, we saw how the convening power of the Secretary-General, and the good relations that developed between the delegations to the UN in New York, offered the venue for negotiations and helped to prevent a nuclear war. To the contrary, in 1994 in Bosnia and Rwanda we saw how, lacking the proper tools to effect peace, the UN was incapable of preventing genocide.

In Syria, the tools at the UN’s disposal would have been sufficient to secure peace but only had the sides involved been willing to compromise. They were not. Ominously, Secretary-General António Guterres said on 18 February at the Munich Security Conference:

I think that peace is only possible when none of the parties to the conflict think they can win. I am not sure we are there yet in Syria. I am afraid that some might still think – and I think that is a total illusion – that they might win that war, so I am not optimistic about the short term solution for the Syrian crisis.

Syria has suffered from the superficial, distorted analysis that almost everyone made of its crisis. A lazy examination of the facts told most people that the regime will disintegrate and fall in no time, the way it did in Tunisia and Egypt. Russia’s voice was the exception, here. But their pronouncements were suspect because of their cosy relations with Damascus. Iran stood staunchly by President Assad and supplied money, food, weapons and militias.

The UN Secretary-General and his envoys alone said, from day one, there was no military solution to the conflict. After around three years of costly war, most people pretended to share the UN view, but that was mostly lip service: they did say that there was no military solution but continued to work for war, not for peace.

The meetings convened in Astana, Kazakhstan, without the UN were useful. Let us hope they will succeed in consolidating the ceasefire they have achieved. But they have had to realise that only a return to the UN might start a credible peace process. It seems that the participants to the Astana meetings have realised that the UN remains the indispensable organisation where serious problems of peace and security are concerned.

The UN is also irreplaceable when entire communities are in need of urgent humanitarian help. In Syria, the UN played a vital role as a deliverer of humanitarian aid to mitigate the suffering felt by the people. But it did only as much as the big powers allowed it to do. Far too often, the Syrian Government prevented UN convoys from reaching large numbers of people in desperate need of help.

The terrible nightmare the Syrian people have lived these past six years is a strong reminder that the UN needs to be given the tools which will allow it to succeed in bringing existing conflicts to an end and preventing future wars. Secretary-General Guterres has been elected under new rules of procedure that allowed a larger participation of the General Assembly and much more transparency than ever before. The Secretary-General is determined to work for more reform, but his reform agenda cannot be implemented without strong cooperation and support from the membership of the Organisation. The reform of the Security Council is particularly important. A good beginning would be an agreement on the restraint of the use of the veto when preventing or resolving a conflict is concerned.

At the time of writing, negotiators are assembling in Geneva. We wish them luck. We hope that the parties and their supporters will hear what Secretary-General Guterres is telling them: thinking that either side will win this war “is a total illusion”. A compromise is possible, and it can be worked out under UN auspices and nowhere else.

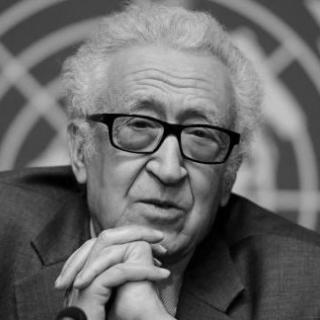

Photo: Lakhdar Brahimi. Copyright UN Photo