Natalie Samarasinghe argues that the organisation is about global governance, not global government

To a world exhausted by war, the promise of the United Nations inspired hope of a secure and long-lasting peace. Its early years raised those expectations further: not only did its establishment mark the end of a conflict, the full horrors of which were then only just emerging, but it also seemed to herald a new era of global co-operation, in which it seemed competing ideologies and interests could be reconciled for the greater good.

Those heady days saw the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on Genocide as well as the beginnings of the UN's humanitarian agencies, such as the children's fund and refugee agency. A decade on from its establishment, the UN had won a Nobel Peace Prize (awarded to the High Commissioner for Refugees), helped to negotiate a ceasefire between the new state of Israel and the Arab countries in the Middle East, and authorised the use of force in Korea.

But the UN's limitations had also become apparent. During the Cold War, the UN Security Council too often seemed frozen when action was needed (it has adopted more resolutions since the 1990s than in the previous 45 years). Korea was in many ways the exception: agreement to act was secured in the absence of the Soviet Union, which was boycotting proceedings to protest against the occupation of the Chinese seat by a delegation from the Nationalist Republic of China.

Then, as now, a tendency to view the Security Council as emblematic of the UN as a whole fuelled perceptions of the latter's impotence. "The United Nations is dead", the Catholic Herald confidently declared in 1947. But to claim that the UN did nothing throughout the Cold War years does great disservice to its achievements. In fact, during this time, the organisation presided over significant developments in international law – notably in human rights and arms control treaties – and its agenda expanded to include issues such as the environment and the life-saving work of its agencies (the eradication of smallpox for example).

The General Assembly also demonstrated that it could take action without Security Council support, calling for a boycott and sanctions against apartheid South Africa. And the UN supported the transition to independence of scores of new post-colonial states, offering them a seat at the global table. To this day, one of the UN's most important roles is as a forum to compel equitable discussion before hasty action – the low incidence of inter-state war since 1945 is no coincidence.

So why the perennial calls for reform? That depends largely on who is doing the calling. Muscular multilateralists invariably want the UN to take robust action. Pacific UN supporters find the use of force and messy on-the-ground activities difficult to stomach. Too many member states, meanwhile, place top priority on resisting encroachment on their sovereignty rather than on effective action to solve shared problems.

Criticism of the UN is often couched in terms of cost or effectiveness. But the sums involved are so small and its effectiveness so reliant on states that these arguments are better understood as resulting from a myth shared by supporters and sceptics. Both are prone to seeing the UN as a "global government", albeit an ineffective one; a thought that is either disappointing or alarming.

The UN was not, of course, conceived as a supra-national government. Its Charter reflects realpolitik as much it does principle, firmly rooted in a system based on the primacy and sovereignty of states. The UN is made up of states and depends on them for its resourcing, leadership and policy direction. It is more plausible to argue that the rise of other actors – regional organisations with stricter membership conditions; corporations and individuals with fortunes bigger than the GDP of certain countries; NGOs; and media with large popular followings – has done more to erode state sovereignty. Any perceived transfer of power that has taken place within the UN system, as a result of treaties, for example, or of the Charter itself, has occurred with the consent of states.

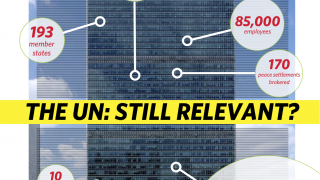

How, then, should we see the UN? The answer depends on which part of the UN one is referring to: member states, officials, intergovernmental bodies like the Security Council, field operations or agencies. On the ground, the UN can be a peacekeeper, aid-giver or institution-builder. In terms of development, it can be a co-ordinator, funder or advisor. At the political level, it can act as a platform for states, a guide to world opinion or an arbiter of military force. Where human rights and justice are concerned, it can be a court, a standard-setter or a forum for holding states to account. Its leadership can, within its many constraints, act as a voice of moral authority. And even this long list ignores the UN's many other roles, such as coordinating postal and telecommunications systems, undertaking research and thought leadership, and producing authoritative statistics.

The sum of these parts is better described as "global governance" than "global government". While the UN's effectiveness rests on how useful it is perceived to be and how much it is used (or ignored) by states, it remains the only international organisation to enjoy such high participation and such robust legitimacy. Even the Security Council, so often criticised for flunking the task, remains pivotal and unique in conferring international authority and pronouncements that are binding on states.

By combining universal membership with privileges for the most powerful, by acting so consistently for the smaller and poorer nations, by increasing access points for other actors such as parliaments, NGOs, and businesses, the UN has for the past 66 years pushed back against the relentless march of national interests. The League of Nations crumbled because it was neither forceful nor attractive enough to keep powerful states at bay. The G20, while (possibly) superior to the Security Council in representativeness, has not yet shown the consistency or effectiveness to make a difference. The European Union, more sophisticated and deeply integrated than the UN, now looks weaker and less coherent.

The fact that the UN has survived should not, of course, lead to complacency. We live in a world of narrowing identities. Regional organisations have shown they can act more swiftly and decisively, and groups of like-minded nations have stepped in where wider consensus has proved elusive. The media – which former UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali referred to as the 16th member of the Security Council – play an important role in generating public support for international action, and this year social media were said to have facilitated political uprisings. Today, companies can have wider spheres of influence than countries and powerful civil society movements are able to mobilise millions of supporters. Avaaz, the web-based campaigning movement that just reported its 10-millionth member, has been described by the Süddeutsche Zeitung as "a transnational community that is more democratic, and could be more effective, than the United Nations". While the impact and endurance of these actors remain uncertain, it is clear that the UN will need to engage them and, where appropriate, harness their support.

Ultimately, though, none of these actors have been able to surpass the UN for its comprehensive membership, its wide-reaching authority or its broad-ranging set of functions. Without it, the world would be a much more dangerous and disorganised place.