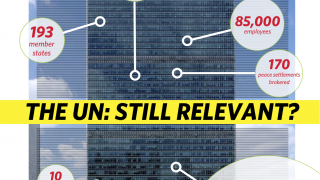

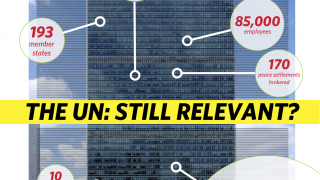

Created in response to the second world war, is the UN still relevant or past its prime?

Surveys such as the Pew Global Attitudes Project, which regularly gauges public opinion in several countries, tend to find a positive response to this question. There are, of course, national variations. The large UN presence and successful UN-led mediation following post-election violence in Kenya in 2007–08 have engendered high levels of approval for the organisation in that country. In Israel, meanwhile, the UN's regular pronouncements on Palestine have fuelled public hostility. But there are some points on which global opinion is more united.

One is humanitarian agencies such as the World Food Programme, which are generally praised for performing lifesaving work with tangible outcomes. In contrast, failure to respond to situations like that in Rwanda in 1994, or to make progress on issues such as the Middle East peace process, can be hugely damaging to the reputation of the UN's political bodies, notably the Security Council. No wonder that its supporters are quick to differentiate between the UN's intergovernmental fora and its agencies and officials.

There is also broad international consensus on the value of the institution as a whole. For several years, polling conducted by Gallup indicates that while the majority of people in the US feel that the UN is not doing a good job, they still want it to play a major role in addressing global challenges. Nearly a third of those polled in 2009 thought it should have a "leading role in world affairs, in which all countries are required to follow its policies".

The gap between the UN's performance and its aims (or, perhaps more accurately, the expectations that attend it) has long coloured perceptions of the organisation. In 1947, just two years after it had been formally constituted, the Wall Street Journal spoke of the UN's "degeneration" and the Catholic Herald anticipated its impending death. Then, as now, the criticisms centred on whether the UN was doing enough to curb national interests or doing too much.

Supporters and detractors have fuelled the myth that the UN can act as a world government. In fact, its member states fund its work, agree its structures, provide its troops, decide its priorities and install its executives. "Blame the member states" might not be a popular answer, but it often goes to the heart of concerns about the UN's cost, composition and efficacy.

These limitations, frustrating for multilateralists, reflect UN's wartime origins. Its Charter is as much realpolitik as principle, firmly rooted in a system of nation states. Only such an organisation could avoid the fate of the League of Nations and so far, the UN has – despite constant (and often unheeded) calls for reform. This should not lead to complacency. In order to remain relevant, the UN must adapt to today's globalised and fragmented world, where a plethora of nonstate actors jostle with states for influence. But at present, no other group or institution can match its reach, legitimacy and impact.

Natalie Samarasinghe

Head of Policy & Communications at UNA-UK