Lawyers often think in terms of cases, and cases are often seen in terms of pitching one set of arguments against another. In truth, sometimes this can be very misleading. There are often considerable areas of agreement between parties and the points that divide them, though critical, can be very fine ones indeed, requiring compromise between the competing interests.

But this is not always so. Some cases involve a clash of ideas which are simply diametrically opposed to each other. When it comes to issues of torture, and of rendition to face torture in other countries, it is vital to be clear that we are dealing with ideas which are fundamentally incompatible with democracy and the rule of law – and there is no room for compromise.

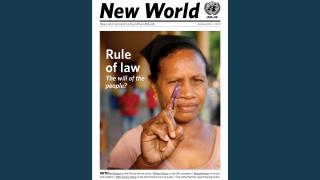

Democracy is, at heart, about living under a system of participative governance – where “we, the people” take centre stage. To live under the rule of law is to live within a system in which laws are applied consistently, openly and impartially. Torture and rendition represent the very opposite of this. Human rights, in many ways, attempt to define the boundary between what the state may and may not do in the common interest, and there is no doubt that one of the foremost principles of human rights law is that which is established in the UN’s Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. Since torture represents the most extreme form of subordinating the individual to the purposes of the state, it is not surprising that it is prohibited in so absolute a fashion. To permit a state to torture an individual is to cross every boundary that the rule of law is intended to protect.

When put in this way, the idea that these problems can be avoided by the simple expedient of sending people abroad to be tortured by others elsewhere – extraordinary rendition – instantly appears for what it is: a shameful attempt to avoid the rule of law, which merely compounds this fundamental incompatibility. What is most worrying, it seems to me, is that those states who claim to be dedicated to democratic governance seemed to have been able to convince themselves otherwise.

And there still remains a degree of ambivalence towards prohibiting the use of evidence which might have been acquired through torture in court proceedings, and a degree of sympathy for the use of such information in the security context.

Some, however, argue that this incompatibility need not be so, and that it is possible to reconcile democracy and the rule of law with such practices. Why not “legalise” torture, if this is what the majority wish – thus making it both “democratic” and a reflection of the rule of law, rather than a violation of it? Even setting aside the point that such domestic laws would violate the international law of absolute prohibition, is it really possible for democracies to legislate to deliberately inflict intolerable pain on people and still have democratic legitimacy? Although we legislate to punish those who break the law, we have long ago abandoned punishing people in such ways as this.

Some, however, argue that this incompatibility need not be so, and that it is possible to reconcile democracy and the rule of law with such practices. Why not “legalise” torture, if this is what the majority wish – thus making it both “democratic” and a reflection of the rule of law, rather than a violation of it? Even setting aside the point that such domestic laws would violate the international law of absolute prohibition, is it really possible for democracies to legislate to deliberately inflict intolerable pain on people and still have democratic legitimacy? Although we legislate to punish those who break the law, we have long ago abandoned punishing people in such ways as this.

Moreover, if a system permits you to torture a suspect, who is to decide if a person is to be tortured? A judge? A prosecutor? An interrogator? On what basis? According to what procedure? And would there be an appeal? To whom? And how? All of this is hardly realistic.

In any case, such thinking flows from too much time having been spent in recent years discussing so called “tickingbomb scenarios” and the ethics of torturing to save the lives of others. No one should belittle the very real and very human dilemmas that can arise. But what is forgotten is that most torture, in most places, most of the time, does not even come close to such scenarios. The truth is that information acquired through torture could almost always have been acquired through other, legitimate, means. More worryingly still, it can be used as a tool for the powerful to overwhelm and intimidate the vulnerable, and thus a tool which democracy not only does not need but that it cannot afford to countenance.

Professor Malcolm Evans is Chairman of the UN’s Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and Chair of UNA Gloucestershire County branch.

Photo: © UN Photo/Christopher Herwig. Nimba county prison inmate looks through a window of a cell during a tour of the overcrowded facility by Henrietta Mensa-Bonsu, Deputy Special Representative of the Secretary-General for the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) for Rule of Law.