On the final day of the Third Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, UNA-UK sat down with Ambassador Tito of Kiribati to discuss ongoing concerns regarding the effects of the UK’s nuclear tests on the island.

Between 1957 and 1962, the UK carried out nine nuclear detonations in Kiribati and facilitated a further 24 U.S. tests, while the territory was under British colonial control. The British and American blasts devastated the island’s landscape with a total yield of around 30 megatons; approximately 750 times the power of the combined bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

While the UK Government “considers its remediation efforts on Kiritimati to have been completed”, this is a unilateral position which is inconsistent with the testimony of affected communities and a growing body of evidence. Ambassador Tito emphasised the need for an independent scientific study to thoroughly assess the long-term consequences. He advocated for the involvement of the Kiribati scientists and community members, UK representatives and international researchers to ensure transparent and credible results. Read the full interview below.

Interview with Ambassador Tito

Ben Donaldson: I’d like to start by reading out the recent UK ministerial response by Catherine West MP of 27 February. It says: “it has been the UK Government's position since 2008 that any remediation work required due to UK nuclear tests in Kiribati has been completed”. What is your response to that?

Ambassador Tito: [...the UK] feels that they have no more responsibility; that they don't have to do anything else. It's nice. But you see that's a one sided story.. It's got to be from us as well. We've got to feel that that is the case. If we don't feel that way then the British government needs to listen to why. We are not ready at this moment, especially with the understanding that everything was done by the British.It doesn't mean we don't trust those who did the work. But it was all done on the one side without us being involved. We want to be involved. If there is information, we want that information to be shared, we want to see it. We also want another study to be done. An independent study of the island. That's what I'm pushing now. A group of scientists, who are independent, who are not attached to any politics. We want the science to be there to look at the island, to look at the health of the people. At present there are many, many issues with health and a lot of people suspect this has to do with the nuclear test. They may be right, they may be wrong; we don't know. But we need the science to tell us. Of course the British have their own science. But whatever their science says, that's the British scientists. We’re talking about having independent scientists and our own scientists working on this which is important so that something comes out that is neutral.

BD: Yes. Independence is vital, isn't it? I read the reports of the cleanup survey that were done in 2007, 2008 that have been used by the UK to say that the cleanup operation is complete. I noticed that there were no tests of the groundwater and what was happening below the ground. And so it was quite a limited assessment that was done in order to give the clean bill of health. Do you have ambitions to do more comprehensive tests?

AT: Yes, There's a group of scientists from a university here in the US who want to do the job. We're just waiting for the government to give the approval for the research for that scientific work to be done, to monitor the level of the radiation and also monitor the health of the people. There are a lot of health issues on the island, especially from the survivors of those, the descendants of the survivors of the nuclear tests.

BD: You mentioned that you don't know one way or another. You're not sure if there's causation. But there seems to be a high sort of incidence of diseases and potentially relevant conditions. What do you think the impact of not knowing is, the impact on people who are suffering from health conditions which they're not sure if they can attribute to the nuclear detonations or not?

AT: It's not good. It's nice to know why. If there's a place which is not safe - maybe the fish or the coconuts or things like that people are eating -they need to know that they should stop eating these things. You see, it's a win, win situation. Once we get things done by science; neutral, independent science, it's a win win for all. It removes the doubts. It's terrible to live under these kinds of doubts.

BD: That makes sense.

AT: Get rid of the crowd of doubts. We must be certain.

BD: That's very, very helpful and interesting and I think that when we relay this back to parliamentarians they will have a much better understanding; a much more human understanding of what you're up against.

AT: Yes.

BD: Because this is about human psychology, isn't it? These are people’s lives that we're talking about.

AT: We have people in Christmas Island thinking about compensation. They're not sure. But how can they go to court if they’re not sure? I believe in facts. I don't believe in people suspecting and then taking cases. I believe in certainty. I believe in science. I studied science myself. That's what I'm talking about.

BD: What was your degree in?

AT: Organic chemistry.

BD: Organic chemistry! I can understand why you're coming at it from this angle. You mentioned a court case in the US earlier on?

AT: Some lawyers here are interested in taking the case to court. I say wait… we should wait until we get the science done first. We want to go to court with scientific data to say this, this and this. We don't want to mislead the court. I don't believe in going to court and pretending there's a case where there's no case. I want to do the right thing. It’s an abuse of the court to go there and make a claim which is not realistic.

BD: That would be playing politics, wouldn't it?

AT: Yes, that's politics. I don't believe politics should be in the court. The court is the court: law, facts, based on facts, sciences. Full of facts, that's my reaction.

BD: Thank you Ambassador this reaction is really helpful….

AT: Of course, I am pleased the UK clean up took place…they did it because I asked Tony Blair about it during the Commonwealth meeting in Edinburgh 1997. He had delegated the issue to his minister. I met him at the dinner hosted by Her Majesty the Queen and he said, yes, the study will be undertaken and It was. I'm pleased it was done. But it was done by the British only. No involvement of the Kiribati people. Now, it was a long time ago. Now, Kiribati has scientists. We have scientists at Harvard university and all over the place. We have scientists who can match the credentials of scientists anywhere in the world. We want them to participate. One of them is in the Scientific Advisory Group, Dr. Parena Kakouzu, based at Harvard University. He really wants that study to be done and he wants to be a part of it.

BD: Have these initiatives been costed yet?

AT: Not yet. That's why we need a voluntary trust fund. The trust fund, we believe, should help finance people to go there. Columbia University is interested to do that, to do the study.

BD: And do you think states like the UK could be part of the solution for helping feed into the trust fund?

AT: Yes. The UK should be involved.We need a combination of scientists; it's got to be neutral. It's got to be done in a way that the people will trust the outcome of that scientific study. It must be neutral and independent of politics.

BD: And also timely, right? It's got to be done fairly soon. Do you think the UK could help fund the trust fund?

AT: Well, it would be nice if they can fund that. Very nice if the UK can do that.

BD: So I'm just looking at, they are cutting overseas aid. I'm not sure how much they're giving the Pacific Forum, but I believe that the funding that they do in the Pacific is through this pooled fund, isn't it?

AT: Yes.

BD: And so I'm not sure whether or not you think that that could be a vehicle?

AT: Yes.

BD: Well, that was really, really helpful. Thank you so much for your time.

AT: All right.

End of interview.

Remediation efforts

A programme to assess and remediate the damage to affected states, including Kiribati, was taken forward by the States Parties of the TPNW via discussion of an international trust fund.

Kiribati has called for the nuclear armed states to engage with this process, not least due to the classified archival material which would be of immense value to any rigorous assessment and remediation programme. Over the next few months UNA-UK will work with members of the Kiribati community to raise awareness of the issue among UK parliamentarians and officials, and ask the UK to rethink its approach to this programme of work.

Read more:

- UNA-UK's briefing on The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

- Dr Becky Alexis-Martin's blog on addressing the harmful legacy of British nuclear testing in Kiritimati

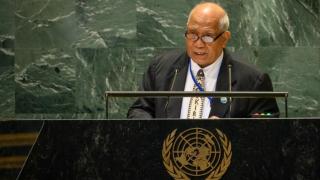

H.E. Teburoro Tito is the Permanent Representative of Kiribati to the United Nations, and former president of Kiribati.

Ben Donaldson is a disarmament expert and advisor on UNA-UK's nuclear disarmament programme.

Photo: Permanent Representative of Kiribati Addresses 79th Session of General Assembly Debate. Credit: UN Photo/Loey Felipe.