This obituary was written for UNA-UK by Edward Mortimer, who worked for Kofi Annan as his Chief Speechwriter from 1998 to 2006 and, additionally, as Director of Communications from 2001.

Kofi A. Annan, who died on 18 August at the age of 80, was the 7th Secretary-General of the United Nations, serving two terms from 1997 to 2006. In the view of many he was also the most successful holder of that office to date, with the possible exception of Dag Hammarskjöld, who died in the service of peace in the Congo in 1961.

Annan was also exceptional in being the first, and so far only, Secretary-General to rise to that office through the ranks of the UN system, having started in 1962 at the lowest professional grade in the World Health Organization.

During that long career he impressed many colleagues and interlocutors with his quiet competence, and also his ability to work on friendly terms with a wide variety of people. Normally that would not be enough to secure appointment as Secretary-General – a decision in the hands of the Security Council, and usually favouring a prominent politician or diplomat with experience mainly serving his own country. But the circumstances in 1996 were unusual.

The Clinton administration in the United States had decided, largely for reasons of domestic politics, not to allow the incumbent Secretary-General, the Egyptian Boutros Boutros-Ghali, to serve a second term. Boutros-Ghali was the first African to hold the office, and the US knew he could only be replaced, politically, by someone from the same continent. Annan, from Ghana, was the senior African in the Secretariat at the time, and had impressed the Americans with his cooperative and pragmatic approach as Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, particularly in the former Yugoslavia.

Many expected, therefore, that he would be a low-key, inconspicuous leader – “more secretary than general”. This proved wrong. Annan saw, like his predecessor, that the post-cold-war-world offered great opportunities to the UN, but also saw that these could be exploited only if approached with tact, caution, and a degree of humility.

Annan saw, like his predecessor, that the post-cold-war-world offered great opportunities to the UN, but also saw that these could be exploited only if approached with tact, caution, and a degree of humility.

With hindsight, one can say that he was fortunate in the time that he came to office. The 1990s were a period of relative harmony among the great powers. With Russia still licking its wounds after the collapse of the Soviet Union and China devoted to a policy of “peaceful rise”, there was no serious challenge to American hegemony, and the five permanent members of the Security Council were able to reach consensus on a wider range of issues than either before or since. This gave an adroit Secretary-General greater freedom of manoeuvre, and enabled him to provide a stronger form of leadership.

At the same time, the twin phenomena that produced globalisation – greater economic openness and the arrival of new, ultra-rapid means of communication – meant that states were no longer the only important actors in the international system, and that a good communicator could reach a global audience far beyond the ranks of governments and diplomats.

Annan seized this opportunity with both hands. He not only set about reforming the Secretariat, but also brought in advisers from outside the somewhat claustrophobic world of traditional diplomacy: notably John Ruggie, a creative thinker about international relations from Columbia University, who became Annan’s strategic adviser for his first four years, and Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland, as High Commissioner for Human Rights.

With Ruggie’s help, Annan focused on the approaching millennium as a chance to bring the peoples of the world together to tackle urgent global tasks – not only in the field of peace and security but also economic development, human rights and even democracy. He persuaded the General Assembly to mark the year 2000 with a summit meeting, and to ask him for suggestions of his own in the form of a report, to which he gave the title “We, the Peoples”.

This contained many recommendations, but eight of them, under the heading of 'development and poverty eradication', were specific quantitative targets for the world to aim at during the next fifteen years, starting with a commitment to halve the proportion of the world’s people living on less than one dollar a day. These were later officially adopted as the Millennium Development Goals.

One of them, to have “halted, and begun to reverse, the spread of HIV/AIDS, the scourge of malaria and other major diseases that afflict humanity”, received Annan’s particular attention. He was acutely conscious of the ravages of HIV/AIDS among the African population, with some parts of the continent in danger of losing an entire generation, and also frustrated by the reluctance of many African leaders to speak openly about it. In 2001 he confronted them directly at a summit in Abuja, and also called for a "war chest” to wage an effective global campaign against AIDS. This led to the creation of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Annan also brought together the heads of the world’s leading pharmaceutical companies, and persuaded them to make anti-retroviral drugs available in poor countries at affordable prices. Many thousands of people must be alive today, notably in Africa, who without this decision would by now have died.

Annan was also active in the more traditional field of preventive diplomacy – a field where successes inevitably get far less publicity than failures. Few people outside Nigeria and Cameroon have heard of the Bokassi peninsula, and that is just as well, since without Annan’s patient diplomacy over several years there might well have been a major war between the two countries over that disputed territory.

Annan came to office with a major albatross round his neck, in the shape of the failure of UN peacekeeping forces to prevent genocide in Rwanda in 1994, and at Srebrenica in Bosnia in 1995. Both these disasters, albeit largely imputable to the unwillingness of troop-contributing countries to take timely action, had happened on his watch as head of UN peacekeeping, and he was never able to live them down.

Annan came to office with a major albatross round his neck, in the shape of the failure of UN peacekeeping forces to prevent genocide ... Both these disasters, albeit largely imputable to the unwillingness of troop-contributing countries to take timely action, had happened on his watch ... and he was never able to live them down.

He did, however, produce a remarkably frank report on the Srebrenica disaster, at the request of the General Assembly, and accepted the findings of an independent commission on Rwanda which he himself set up, and which came down hard on the Secretariat’s responsibility, including that of Annan himself.

He also commissioned a major report on UN peacekeeping in general, from a panel headed by the distinguished Algerian diplomat, Lakhdar Brahimi, as a result of which peacekeeping forces now generally have a much more “robust” mandate than heretofore to protect civilians, and the Secretariat has adopted a policy of “telling the Security Council what it needs to know, rather than what it wants to hear”.

But Annan was well aware that peacekeeping forces would never be equipped to fight all-out wars, and he sought, through a series of speeches and other interventions, to confront member states, particularly those on the Security Council, with their responsibility to protect civilians from genocide, ethnic cleansing, war crimes and crimes against humanity, even when these atrocities were being committed by states within their own borders. This doctrine was in due course formulated by an independent commission set up by the Canadian government, and in 2005 adopted formally by the General Assembly meeting at summit level.

The end of Annan’s first term was marked by the terrorist attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001, which led to a marked change in the international climate. Partly to try and forestall excessive responses, in the following month the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded its Peace Prize to Kofi Annan and the United Nations.

At the same time a coalition led by the United States invaded Afghanistan and overthrew the Taliban regime, which had refused to extradite the presumed author of the attacks, Osama bin Laden. This action enjoyed general international support, including from the Security Council, and led to a new Afghan government in whose creation Lakhdar Brahimi, as Annan’s special representative, played a key role.

But the US then turned its attention to Iraq, seeing the new atmosphere as propitious for a military solution to the long-running problem of Saddam Hussein’s failure to implement fully the terms of the ceasefire imposed on him by the UN in 1991, particularly as concerned cooperation with UN inspectors seeking to verify that Iraq no longer maintained an arsenal of weapons of mass destruction.

The US and its allies were not, however, able to convince the international community at large, including most of their colleagues on the Security Council, that this problem had any connection with the 11 September attacks, or that the inspectors, armed with a strengthened mandate under the Swedish expert Hans Blix, should not be given more time.

Annan’s pleas to stick to a multilateral approach were disregarded, and in March 2003 the invasion went ahead without authorisation from the Security Council – which, as Annan said, was “not in conformity with the Charter”. (He later used the word “illegal”.) But he was anxious to show that the UN could still be useful, notably to the Iraqi people, even in these adverse circumstances, and in May was persuaded to send Sergio Vieira de Mello – perhaps the UN’s most able administrator – to head a new UN mission in Baghdad.

Outside the heavily fortified US “green zone”, this mission was accessible to ordinary Iraqis, but alas also to those determined to resist violently any international presence that might seem to legitimise the occupation. On 19 August 2003, the mission’s headquarters was blown up by a suicide bomber driving a truck full of explosives. Vieira de Mello himself perished, along with 21 other UN staffers. It was a bitter blow for Annan, who could not escape the knowledge that he had sent close friends and colleagues, including some of the Organization’s best and brightest, to their deaths.

Bitter too were the attacks that rained down on him, throughout 2004 and 2005, from American journalists and politicians who sought to distract attention from the increasingly dire consequences of the invasion by focusing on evidence of corruption in the Oil-for-Food programme, intended to palliate the effects of UN sanctions on Iraqi civilians, which the UN had administered from 1996 to 2003.

These attacks became increasingly personal when it emerged that Annan’s son Kojo had worked for a Swiss company charged with inspecting the consignments of food and other humanitarian supplies which Iraq was allowed to import. Kojo’s work had had nothing to do with Iraq, and there was no evidence that Annan had played any part in getting him the job, but his claim not even to have known that the company was competing for the contract was widely disbelieved, and it was clear that when this fact did come to light he had not handled the affair with sufficient rigour.

Although Annan was eventually exonerated by the inquiry chaired by Paul Volcker, former head of the US Federal Reserve, there were many attacks on him in the press, and even calls for his resignation from at least one US Senator. He survived to serve out his term, but was clearly weakened and more dependent than previously on the support of the US administration.

The end of 2004 marked a low point when he seemed close to giving up, but in 2005, supported by a new chef de cabinet, Mark [now Lord] Malloch Brown, Annan was able to re-focus international attention on the summit held in September that year to review progress since the millennium, which adopted some important reforms including, as well as the Responsibility to Protect, the creation of the Human Rights Council and Peacebuilding Commission.

His last year, 2006, was marked by renewed conflict in the Middle East between Israel and the Lebanese Shia movement Hizbollah. Annan had earned gratitude from Israel by supporting its right to membership of a regional group in the General Assembly, certifying its withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000, and encouraging the Assembly to adopt January 27 as an annual day commemorating the victims of the Holocaust. But he could not in conscience go along with the US and Britain’s willingness to condone Israel’s attempt to impose a new order in Lebanon by force, and won little thanks for eventually helping to extricate Israel from a mess of its own making, by negotiating a ceasefire which included a stronger UN buffer force in southern Lebanon.

None the less, by the time he left office Annan’s international prestige had recovered, and not long afterwards the African Union turned to him to lead a peacemaking panel in Kenya, where he succeeded in averting a serious threat of ethnic violence in the aftermath of the 2007 elections.

After leaving New York he settled in Geneva, where he set up his own Foundation close to the Palais des Nations, and used it to further a range of causes including the improvement of agriculture in Africa and the introduction of safeguards to ensure free and fair elections in different parts of the world.

He and his wife Nane, who had been a tower of strength for him throughout his time in office, felt at home in Switzerland, where both had spent a large part of their professional lives, and indeed had met when working for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees in the early 1980s. Their love for the country was reciprocated, and it was hardly a coincidence that it was during Annan’s term, in 2002, that the Swiss people decided in favour of full UN membership.

In 2012 the international community, in the shape of the UN and the League of Arab States, again had recourse to Annan’s diplomatic talents, jointly appointing him as a mediator in the Syrian civil war. He threw himself into this task and produced a six-point plan which was accepted by the main parties to the conflict, but was unable to get it implemented – largely thanks, once again, to divisions among the permanent members of the Security Council.

In August 2012 he abandoned the effort, preferring to concentrate on his other work, which included from the following year serving as chairman of The Elders, the group of international elder statesmen and women launched by Nelson Mandela in 2007. He also served on the boards of several foundations and, right up to his last month, travelled the world indefatigably, seeking to promote the causes of sustainable peace and development that were so close to his heart.

Born on 8 April 1938 in Kumasi, Ghana, he died in Bern, Switzerland on 18 August 2018, mourned by his wife Nane, their children, Ama, Kojo and Nina, and several grandchildren – but also by many throughout the world who valued his contributions to world peace and hope to see his legacy maintained and continued.

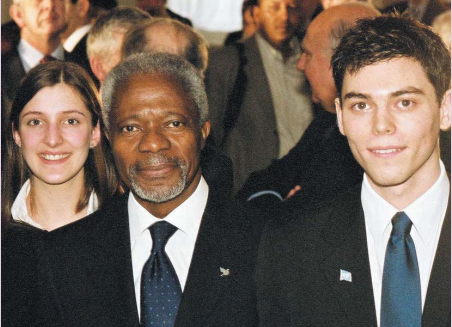

Photos: Kofi Annan at UNA-UK events. Credit: UNA-UK