David Malpass was elected as President of the World Bank Group on April 5 2019 for a five-year term starting on April 19 2019. However, on February 15 2023 he announced his intention to stand down early on June 30 2023. An election to be held shortly before then will determine the new President.

While a number of names had been informally mentioned as seeking the US’s nomination including Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, (who has subsequently gained US citizenship), Raj Shah, Gayle Smith, Samantha Power, Simon Walley, Alexis Taylor, and John Kerry, on Thursday 23 February the US formally announced the nomination of Ajay Banga.

What is the World Bank Group?

The World Bank Group is a consortium of five different international organisations: the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID).

These organisations are International Development Banks and associated programmes. They pool capital contributed by its members for the purposes of making loans to further its objectives of ending extreme poverty and building shared prosperity. However, unlike other international financial organisations like the IMF, the World Bank expects to lose money on its work over the long term, and for its members to recapitalise its fund from time to time.

What is the relationship between the World Bank Group and the UN?

Three of these organisations are specialised agencies of the UN, while two are not. This means that 3/5ths of the World Bank Group has been brought into association with the UN as a Specialized Agency under articles 57 and 63 of the UN Charter - and thus have a reporting relationship with the UN’s Economic and Social Council, while the other 2/5ths are fully independent of the UN. However the World Bank Group as a whole, in the form of its President, sits on the UN’s Chief Executives Board, which is a group - chaired by the UN Secretary General - with responsibility for coordinating action across the UN System to achieve the Sustainable Development goals.

How is the World Bank Group Governed and how is the President elected?

While each of the five organisations within the World Bank Group has its own different (if frequently similar and overlapping) governance structure, the President of the World Bank Group is chosen by the IBRD, according to its rules, and is then placed in overall charge of the five organisations.

The IBRD is an international organisation of 189 member states founded in 1944 and made a Specialised Agency of the UN in 1947. It is governed by the IBRD articles of agreement and further by-laws under which the President is elected by the Executive Directors for a term of five years, renewable for that length of time or less without limit.

There are 25 Executive Directors but they don’t all have equal votes: states own shares in the IBRD on the basis of how much they have invested in it and each Executive Director is able to cast a number of votes equivalent to the number of shares held by the states that have pledged their support to that Executive Director.

To be elected the President of the World Bank, a candidate needs to receive over 50% of the vote from Executive Directors. In other words they need the support of a group of Executive Directors who, between them, hold 50% of the shares in the world bank.

Who are the 25 Executive Directors and how are they chosen?

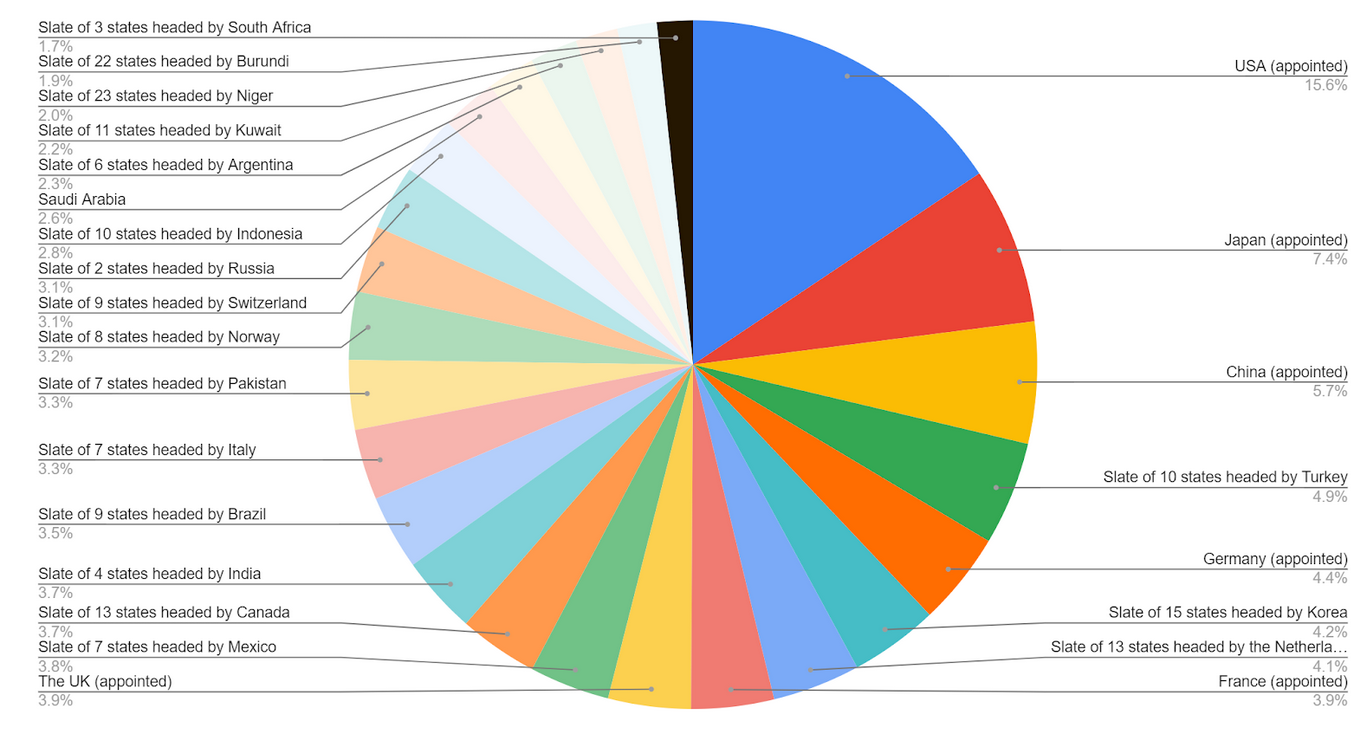

The five largest shareholders are able to appoint an Executive Director automatically, but as two shareholders are currently tied for fifth place that means currently six states appoint Executive Directors this way: the United States, Japan, China, Germany, France and the United Kingdom. The other 19 (in usual times 20) Executive Directors are elected by the remaining shareholders.

A small number of states hold enough shares that they would be able to elect an Executive Director to represent them on their own, but currently, only Saudi Arabia chooses to do this. Instead, all the remaining states have organised themselves into a number of electoral slates whereby states pool their shares in support of a joint Executive Director. The number of slates is organised to exactly fill the number of available vacancies. In this way states ensure that they all get representation in some form, even if it is only in the form of being part of a coalition behind an Executive Director; and they ensure that the 25 Executive Directors are between them able to cast all the votes that are available to be cast.

Such slates can consist of as many or as few states as states wish. States weigh up the pros and cons of being able to exert more influence within a smaller slate with having a greater number of total shares pledged and thus voting power as part of a larger slate. In addition, states need to be confident that the Executive Director their particular slate backs will pursue an agenda they support at the World Bank.

The full list of Executive Directors, the voting power each one holds, and the states that back each one is available here, and is also shown in the pie chart below.

Why is the President of the World Bank Group always an American Man?

There is absolutely no reason why the President of the World Bank Group should be a man, and it is disgraceful that all the previous 13 Presidents have been.

The structure of the World Bank means that the President is very likely to be an American - or at very least the candidate that America backs. The United States is the largest shareholder, and its Executive Director singlehandedly controls 15.63% of the vote - more than double that of any other shareholder. Furthermore the US has an informal agreement with France and Germany (two of the other largest shareholders) and with European shareholders more broadly, whereby they will back a French or German candidate to be Managing Director of the IMF in exchange for support at the World Bank.

This agreement guarantees any US candidate a quarter of the vote before they even start campaigning, and when one adds in the support of other Executive Directors who owe their allegiance primarily to Europe a US candidate will find they are able to control close to 50% of the vote without having to make much effort. In contrast any rival candidate faces a near impossible task in piecing together a winning coalition involving large numbers of Executive Directors almost all of whom will only be able to support them if their sometimes large and disparate slate of supporting member states can agree to do so.

For this reason the President of the World Bank Group has without fail been the candidate nominated by the USA and attempts to seriously challenge the US nominee are very rare. Even controversial appointments like Paul Wolfowitz in 2005 who were informally challenged robustly were ultimately adopted unanimously by all 25 Executive Directors when it came to a formal vote.

Thus far the sole exception was in 2012 when a US candidate, Dr Jim Yong Kim, was challenged by a Nigerian Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala (she has subsequently taken US citizenship, but did not have it at the time) with the backing of the African Union and many developing states and Colombia’s Jose Antonio Ocampo, backed by much of Latin America. Ocampo quickly withdrew and supported Ngozi. Following an informal vote in which Kim was victorious, a formal vote was taken and almost all Executive Directors decided to support the American. Only an unknown but small number of Executive Directors, collectively holding less than 20% of the vote, refused to do so. This result was not made public, and was officially acknowledged only in that for the first time in history the press release announcing the President’s victory did not use the word “unanimous”.

How can this process be improved?

A recent briefing by the Congressional Research Service highlighted the almost complete absence of due process in the processes leading up to the vote on candidates for President of the World Bank.

While the WBG may have only a tangential relationship with the UN as an institution, it is very much part of the same international system and the selection process is prone to the same deficiencies the UN faces. Government support and lobbying, not competence, will be the prime deciding factor in the appointment. While this is hardly an underhand scheme - the constitution more or less guarantees it - it is far from optimal. It is high time the process was reformed to add transparency, accountability and inclusivity into the process.

Although unlikely to happen soon, in the long term there is an argument to be made that the World Bank Group should move its governance away from the shareholder model and towards one that gives the people the World Bank’s projects impact as much of a say as the people who pay for it. The Global Vaccines Alliance (GAVI) provides an interesting model here.

In the absence of constitutional reform, lessons can be learnt from the 1 for 7 billion process for reforming the Selection of the UN Secretary General whereby candidates are pushed to publish a vision statement and present it to all member states and civil society to help stakeholders engage how they will perform in their role. And much as the straw polls for the selection of the UN Secretary-General should be published and, in the absence of that, were routinely and reliably leaked, so too any votes, formal or informal, for the Presidency of the World Bank, should be published and should be leaked if they are not.

Before the US announced its nomination of Ajay Banga, we made the point that as it stands, the candidate with the backing of the USA will win. This therefore places a special responsibility on President Biden. If he is in effect choosing the President of the World Bank himself then he owes it to the world to emulate international standards of best practice for senior appointments in making his choice. We made the case that he should be accountable and transparent at every stage of his decision-making process.

Moreover, there is no obligation for the candidate nominated by the US to be a US citizen, and the best interests of the United States would be best served by having the best possible President of the World Bank Group. For this reason we had hoped that President Biden would mount an international search based on a competitive, open process, and nominate the best possible candidate for the job, regardless of their nationality.

Read more

- Subscribe to Blue Smoke, the newsletter tracking senior UN appointments

- See the comprehensive list of roles in the UN’s Senior Management Group

- Read the comprehensive list of roles in the the UN’s Chief Executives Board

Photo: World Bank Group Headquarters during the Annual Meetings (2019). Credit: World Bank / Grant Ellis / Flickr