UNA-UK's Policy & Advocacy Officer, Hayley Richardson, has recently returned from a visit to the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva. Read on for her report.

In Geneva for just three short days, I was eager to get a real sense of how the UN's human rights system operates in practice. In theory it's a series of institutions and mechanisms designed to promote and protect human rights. The Human Rights Council (HRC) is the primary UN body for raising the alarm on situations of serious concern. Its Universal Periodic Review mechanism is unique at the UN for its systematic assessment of the human rights record of every single member state. And the Treaty Bodies - the various committees which monitor the implementation of international human rights treaties - provide valuable guidance on how to translate sometimes abstract concepts into practical legal protections.

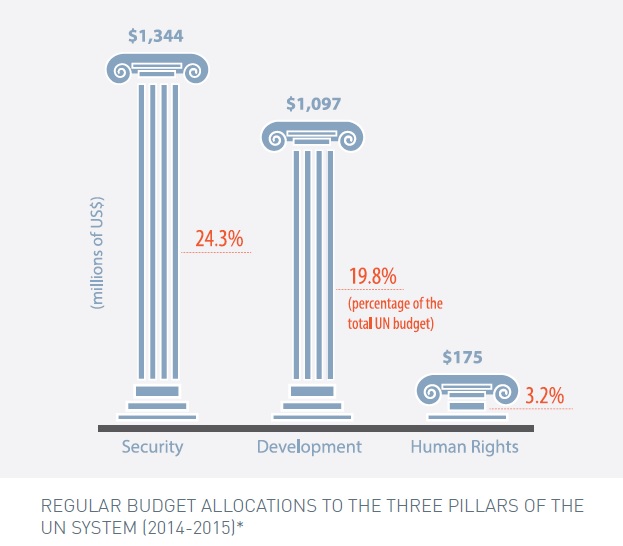

In reality, this labyrinthine system is under-funded and over-loaded. Receiving just three per cent of the UN's regular budget (see Universal Rights Group's infographic, left) the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is at full stretch. Acutely aware of this, the recently appointed High Commissioner Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein used the 28th session of the HRC to announce a restructuring of OHCHR.

In reality, this labyrinthine system is under-funded and over-loaded. Receiving just three per cent of the UN's regular budget (see Universal Rights Group's infographic, left) the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is at full stretch. Acutely aware of this, the recently appointed High Commissioner Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein used the 28th session of the HRC to announce a restructuring of OHCHR.

Major changes include establishing seven new regional hubs, strengthening the capacity of the New York office and a reorganisation of the divisions in Geneva. The High Commissioner stated that the changes will "make us more effective in protecting and promoting human rights, and in discharging our mandates as called for by relevant organs and sub-organs of the UN. It will also generate savings, which we will be able to re-invest in core activities".

This announcement was welcomed by many of the diplomats and NGO representatives that I spoke with, though judgments will be reserved until further details of this plan are made public. The timing of the announcement, though, was interesting. It coincided with the expected HRC consideration of a report from the UN's Joint Inspection Unit (an external oversight body) which raised fundamental questions about the governance of OHCHR. Backing the long-running concerns of Cuba over what they perceive as a Western-bias at OHCHR, the report recommended that member states play a much stronger role in the management and administration of the Office. Much of the report's findings had already been rejected by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon as at odds with the High Commissioner's fundamentally independent mandate.

Technical, but sensitive, issues such as these are not exclusive to the HRC, but are certainly typical of its inherently political nature. Whilst it has undoubtedly made a positive contribution to the promotion and protection of human rights, as an intergovernmental body of 47 states, many of the HRC's decisions are affected by outside interests.

With universal participation, the UPR is considered the most even-handed of the UN's human rights mechanisms, yet states often use the process to put forward politically-motivated recommendations. Even bureaucratic procedure can be co-opted. At the UPR outcome session of Iran, I witnessed Oman, Sudan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Venezuela and others congratulate the Iranian Government on its laudable human rights record. The UK and US seemed to be rare dissenting voices. Diplomats informed me that it was common practice for countries to fill the ballot box of nominations for oral interventions with friendly states in a bid to lower the likelihood of embarrassment.

One valuable source of input that states find harder to quell is that of civil society. 10 NGOs gave their own assessments of Iran's human rights record at the outcome session. Yet more provided written statements. This interaction was one of the most positive features I took away from my experience in Geneva. The involvement of civil society appeared to be much more embedded than in other parts of the UN that I've experienced. With my NGO pass in hand I was able to wander in and out of HRC deliberations as easily as I did the cafeteria on the floor below. Of the average 8am-7pm packed schedule of events, only around an hour was out of bounds to NGOs (at private negotiations in regional groupings). At every other discussion, NGOs were at the table. With so much strain on this vital system, the input, support and expertise of these independent voices must surely grow.