Part of our regular series of background briefings on the UN in the news.

Secretary-General Guterres has announced wide ranging reforms of the UN system. Just over a year into his term we look at the three main strands of reform he has announced so far: to the UN’s development and peace and security pillars, and to the UN’s management.

Here’s what has been announced so far, and what we can expect.

Peace and security

What’s happening?

The Secretary-General published a “white paper” on peace and security in October 2017. This outlined his thoughts on the issue and was circulated to member states for feedback. States have been broadly supportive: the UN Security Council (which, along with all member states had advance sight of the paper) signalled as much in a resolution in September 2017 and the General Assembly did the same in December 2017.

The white paper announced that a second white paper would appear in December with further details but this has yet to appear. The General Assembly resolution backing the reforms did ask for a “comprehensive report” to be prepared as soon as possible and it is likely that this will replace the second white paper. The President of the General Assembly has announced a high-level event to discuss the reforms on the 24-25 April which indicates the comprehensive report should appear soon, and certainly in advance of the event.

What does the reform entail?

Under the proposals the roles previously held by the Department for Political Affairs (DPA) and the Department for Peacekeeping Operations will be shuffled into two new but still separate departments: the Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) and the Department of Peace Operations (DPO). These two departments would then co-manage three regional Assistant Secretary-Generals (ASGs) and their teams, each of which would have combined responsibility for political and peacekeeping missions in their area.

These two new departments will be tasked with leading a “surge in diplomacy for peace” while a wide reaching “prevention agenda” will ensure that preventing violent conflict and protecting human rights is hard wired into every part of the Secretary-General’s work

What effect will it have?

The idea is to have the ‘best of both worlds’ combining the strengths of having two separate departments in New York with the strengths of having one united focal point for work on the ground.

The idea has considerable merit, but will require careful implementation. In particular, the new structure could create many overlapping lines of accountability and authority.

In terms of substance UN peacekeeping could certainly be done in a different, and cheaper, way. A smaller mission staffed by highly trained and disciplined troops could be as effective as a much larger mission. But the transition to this new kind of peacekeeping must be handled with care, or else civilians in some of the worlds’ most at-risk regions will pay the price for a failed transition. This is an issue UNA-UK has written about previously.

It is also unclear how this plan will be able to adapt to a potential, if now less likely, new UN mission in Eastern Ukraine, and the United States’ intention to limit its funding to 25% of the total peacekeeping budget, putting them into arrears and leaving peacekeeping with a near $300 million shortfall. These factors will certainly influence the decisions member states make about future funding by July 2018.

Development

What’s happening?

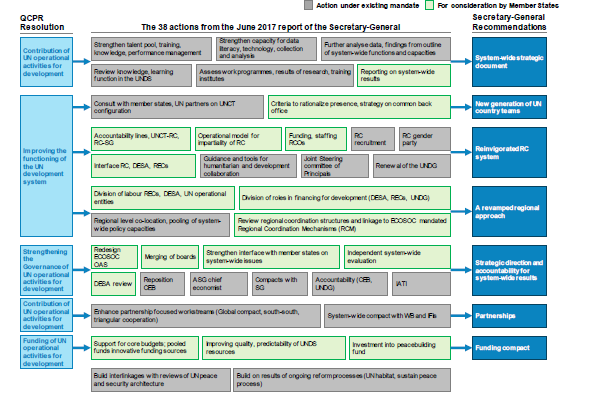

The Secretary-General released a white paper in July 2017 and subsequently released a comprehensive report in January 2018. This comprehensive report lays out many reforms which can be achieved right away within existing mandates – in particular on reshaping regional development structures – as well as requesting that this year member states give him the mandates to achieve the more fundamental changes the reform outlines.

What does the reform entail?

The reform process is sevenfold.

- From now on the strategy for development across the entire UN system will be aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) - the 17 targets for 2030 that member states agreed in 2015. A system wide strategic document will ensure that all UN action on development is linked to the SDGs.

- Within each country the UN operates there is a UN Country Team (UNCT) which is tasked with creating a development assistance framework (UNDAF) under the control of a Resident Coordinator. This mechanism will be enhanced to the point where the UNDAF is “the single most important UN country planning instrument” and where the UNCT will become central to the workflow of all UN partners. This will closely integrate the work of the various UN Departments, Funds, Programmes, and Specialized Agencies into a common agenda with a common office.

- The role of the Resident Coordinator (RC) will be de-linked from the UN Development Programme (UNDP) which previously provided the RCs. This is something that UNA-UK has long called for, particularly in crisis and conflict situations where the UN’s role is primarily non developmental. UNDP will have a Resident Representative, who will be part of the UNCT but the RC will be able to overrule them on all matters including the content of the UNDAF.

- Regional leadership, and line management for the RCs, will be provided by a new UN Sustainable Development Group Office (SDGO) chaired by the Deputy Secretary-General. In addition, the SDGO will take a strongly regional approach complimented by a revamped Department for Economic and Social Affairs and repurposed Regional Economic Commissions, which will somewhat act as regional think-tanks.

- New life will be breathed in to the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) which will be tasked with ensuring improved strategic guidance, transparency and accountability.

- Six new mechanisms for strengthening partnerships with the private sector and civil society

- A new funding compact to be agreed by the end of the year, under which the UN would promise increased transparency and accountability and member states would promise to earmark less of their funding and give the UN greater flexibility over how and where it is spent. The Secretary-General has asked for full funding of the SDGs agenda (an extra $980 million over the next five years), for the amount of funding that is not earmarked to increase from 21.7% to at least 30% and for the amount of earmarked funding that goes to interagency pooled funds to increase from 8% to 16%.

What effect will it have?

This is the first time the work of the UN has been so comprehensively linked to a set of goals like the SDGs. The SDGs predecessors, the MDGs, were not integrated into the work of the UN to nearly the same extent. This is undoubtedly a positive step.

The management reforms also appear positive: providing local flexibility and regional expertise and, most importantly, linking the UN’s development role with its wider political work and ensuring that the development system answers to the Secretary-General. This is vital, as we have previously written about the structural risks of the UN’s development work prioritising access at the expense of politics, and so exacerbating conflict situations and the risk of atrocities.

The commitment to full and comprehensive gender equality is also welcome.

However there is cause for concern in that this comprehensive strategy document makes no mention of the Secretary-General’s Human Rights up Front (HRuF) initiative and that human rights only receives six cursory mentions in the report. While it is positive that the UN’s development and peace and security work will be better integrated in future, its human rights work also needs to be integrated. Moreover, comparing the Secretary-General’s July and January papers the more recent paper heavily emphasises the extent to which Resident Coordinators will and should rely on the advice and expertise of the UNDP resident representative. It also stresses that UNDP will be at the heart of the country teams, and will provide all administrative support for the Resident Coordinators.

This raises concerns about how big of a change the new structure will really make, and highlights the risk of change becoming cosmetic. The HRuF approach has been successful in better integrating human rights, politics, peace and development at a regional level - but translating this to the country level requires a country approach in which these areas of work are given equal importance. Peace and Development Advisors (PDAs) have helped promote this approach in the countries they have been deployed to and expanding the programme would be a positive step.

Further, while more money is certainly needed, and while the Secretary-General is right that greater flexibility in funding is required, in the long term there is a strong argument that the UN should be seeking to step back from delivering frontline services, and instead supporting other better placed actors, while focusing on doing what only the UN can do: facilitating, convening, encouraging, advising and monitoring states and other implementers. This proposal does not set out a vision for what the UN’s work might look like in 15 years, at the end of the SDGS “Agenda 2030”, or explain how to focus an expanding agenda which is already placing limited resources under pressure.

Management

What’s happening?

The Secretary-General proposed various management reforms in a white paper in September 2017. In December 2017 the UN General Assembly’s fifth – financial – committee approved many of them on a trial basis for the year of 2020 (the 2018-19 budget having already been agreed) while tasking the Secretary-General with writing a comprehensive report on his proposals for discussion in May 2018.

What does the reform entail?

The principle parts of the agenda are as follows:

- Moving the UN from setting a two-yearly budget to an annual one

- Replacing the sometimes clumsy, multi-part and overlapping five-to-seven year sequences of the UN Planning, Programming, Budgeting, Monitoring and Evaluation cycle (PPBME) with a simpler three year planning cycle

- Establishing two new offices tasked with reducing duplication: a Department of Management Strategy, Policy and Compliance and a Department of Operational Support. In addition, the current Department of Management and Department of Field Support would be merged in to a new Department of Management and Field Support, with responsibility for all recruitment.

- Consolidating various administrative functions into two or three global centres, and closing the administrative sections of the UN’s other offices

- Increasing the Secretary-General’s discretionary “working capital” fund from $150 million to $350 million and increasing the Secretary-General’s ability to make other discretionary changes to budgets mid-year in response to “unforeseen and extraordinary expenses”

- Better IT and supply change management linked to stronger auditing, through a new IT system called “Umoja”.

What effect will it have?

While the idea of creating two new offices to reduce duplication may seem ripe for parody, overall these are much needed, long overdue and highly positive reforms. The current system is unwieldy. Speaking at an event we hosted in London the Secretary-General described it as “a conspiracy to make … the UN non-operational” – these reforms would go a long way towards thwarting that conspiracy. The issues will be in implementation and in detail, and we look eagerly to the Secretary-General’s comprehensive report in May.

The suggestions perhaps do not go far enough in the field of human resources. At the same event the Secretary-General said, “I am not allowed to create one position – a technical position in one office in Geneva for instance – without going to the General Assembly and having the consensus of 193 countries, and the same to abolish that position.” Former United Nations Assistant Secretary-General for Field Support Anthony Banbury said “it is virtually impossible to fire someone in the United Nations”. This needs to change; the Secretary-General’s white paper says only that these are complex issues which require further study. The comprehensive report will go further.

Finally, while much can and should be done without the UN General Assembly’s approval, some of the most difficult but important reforms will require approval by states. There is a risk of states not recognising the overall strategy and cherry picking the reforms they like. This could have the effect of further constraining the Secretary-General, leaving him without the flexibility to deliver the cheaper and more efficient UN that states want.

What’s missing?

Former UN Acting High Commissioner for Human Rights Bertrand G. Ramcharan recently wrote an article sharply criticising the absence of a human rights based reform proposal. One could argue that this is because the human rights pillar faces problems with chronic underfunding and a lack of political support, but the architecture itself is working well in trying circumstances – it has been only 13 years since the last comprehensive reform of the UN’s human rights system.

Nevertheless, it is vital that human rights not be left behind in the reform process, and this is a point which we hope the new UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, to be appointed in the coming months, will make.

Photo: A tower of scaffolding is visible alongside UN Headquarters’ Secretariat building as renovations take place in 2011, UN Photo/Rick Bajornas