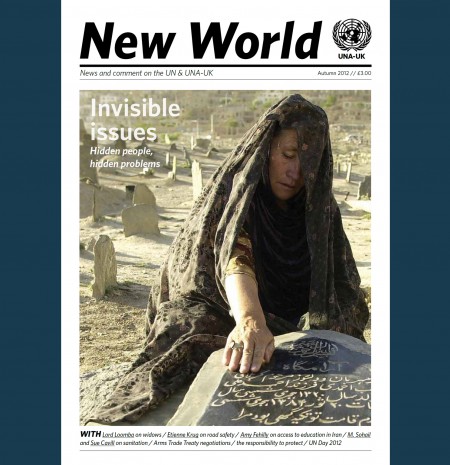

“The responsibility to protect is a concept whose time has come. For too many millions of victims, it should have come much earlier” Ban Ki-moon, UN Secretary-General

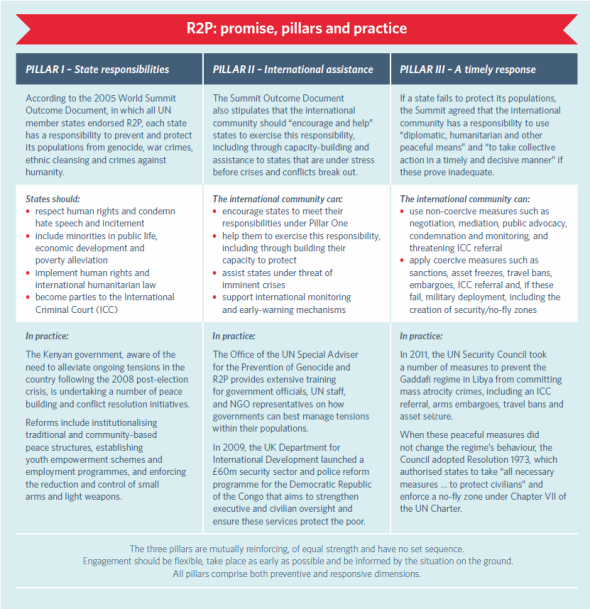

The responsibility to protect (R2P) provides a framework for preventing and halting four crimes that shock our moral conscience and threaten international peace and security: genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing. Adopted unanimously at the UN World Summit in 2005, the principle affirms that each state has the responsibility to protect its populations from these crimes, and that the international community has an obligation to provide assistance to states at risk, and to respond in a timely and decisive manner if prevention and assistance are unsuccessful. A plan for implementing R2P was outlined by UN Secretary-General Ban Kimoon in 2009, which separated the principle into three sections, or “pillars” (see box below).

Although the three pillars comprise a large variety of tools, from institution-building to human rights promotion, mediation to fact finding missions and economic sanctions to arms embargoes, R2P is often misunderstood as a synonym for military intervention – a measure that can be utilised, but only when all peaceful means have been exhausted. Several states, and indeed NGOs, view the principle as an extension of the divisive humanitarian intervention doctrine of the 1990s (the “right to intervene”), rather than a continuum of engagement and assistance firmly anchored in state sovereignty. Media coverage generally reinforces this perception, focussing on cases where intervention is being considered, which is symptomatic of the wider prioritisation of conflict resolution over prevention.

R2P provides for a much broader approach, also prescribing longer term capacity building and non-coercive measures in the second pillar that can be implemented without requiring UN Security Council authorisation. For the general public, these preventive actions remain largely unnoticed – unreported, vaguely understood and, for all intents and purposes, invisible.

The following examples provide an insight into the diverse and crucial work taking place behind the scenes, both in the field and in terms of policymaking. Nonetheless, when a crisis looms, longer-term assistance initiatives need to be supplanted by more direct preventive measures, as described in pillar three.

There are, of course, legitimate concerns about the misuse of the military measures in this pillar. Disagreements about the interpretation of UN Security Council Resolution 1973 on Libya, in particular NATO’s subsequent actions in the country, have had an inhibiting influence on the Council’s approach to preventing mass atrocities in Syria. Fortunately, member states are beginning to engage in fruitful discussion on regulating and monitoring the use of force, with Brazil advancing a concept in the General Assembly calling for “responsibility while protecting”.

As it is only the coercive dimension of R2P, specifically the use of force, that causes controversy, the Security Council’s current divisions represent a failure of politicalwill, rather than a failure of the R2P principle. Long-term, structural prevention of mass atrocities is not beholden to Security Council agreement and there is a wide spectrum of action that governments, UN agencies and civil society organisations can take. The vital behind-the-scenes work to prevent mass atrocities demonstrates the principle’s continuing relevance, and its utility in tackling some of the root causes of these egregious crimes.

Nevertheless, it is essential that the international community continues to discuss the application of the more robust features of R2P in order to bolster efforts to persuade and dissuade states unwilling to uphold their responsibilities. Only when there is a credible threat of the use of force that can be applied legitimately will the international community possess the diplomatic leverage to be truly able to move R2P from promise to practice for short-term, imminent and ongoing threats.