This year marks the 20th anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda, which saw some 800,000 people killed in just 100 days of slaughter. The Rwandan genocide played a strong part in motivating governments to adopt unanimously the responsibility to protect (R2P) principle at the 2005 UN World Summit.

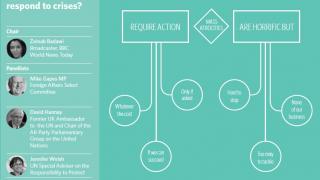

R2P holds that there is a collective responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. States bear the primary responsibility for protecting their populations but the international community has a duty to support them in exercising it. If a state is unable or unwilling to do so, then the international community can take a range of measures.

The most contentious measure – the use of military force – has a number of limitations. It should only be used when all other means have been exhausted, must do more good than harm, result in as little violence as possible and have a reasonable chance of success. It also requires authorisation by the UN Security Council.

Since then, states have struggled with when and how to implement this responsibility. In countries such as Sudan and Sri Lanka, the international response was largely confined to hand-wringing. In Libya and Mali, robust action was taken but not without criticism. In Syria the death toll continues to rise in the absence of adequate action.

As a permanent member of the Security Council, the UK has an important role to play in helping the international community to respond to atrocities. But politicians and the public have different views on what form this role should take. Last year, the UK Parliament narrowly rejected possible UK military action in Syria. The vote was thought to broadly reflect public opinion, but polling shows a more nuanced picture.

43 per cent of respondents in our YouGov poll felt that it was right to send British troops to take military action for humanitarian reasons. In a survey we commissioned from Ipsos MORI in 2012, 25 per cent agreed that the UK should intervene if there is “even an indication that civilians are at risk”.

Guided by Zeinab Badawi and questions from participants, our panellists discussed whether, and how, the international community can address mass atrocities. Their main points are summarised here. Visit www.una.org.uk/forum for the full recording.

Q: Does responding to crises using military intervention increase the risk of human rights violations? (Farvah Javaid)

David Hannay (DH): I don’t think that we can seriously say that if there had been military intervention in Rwanda there would have been more human rights abuses than took place in the genocide, or if force has been used earlier in Srebrenica, that it would have led to more violations. Just because we cannot protect everybody all of the time, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to protect anyone.

Mike Gapes (MG): It depends very much on what happens afterwards. If, for example, we look at Libya today, clearly the situation is terrible. Does that mean that stopping Gaddafi from massacring people was wrong? No. But there are issues regarding the aftermath – how we deal with ungoverned areas, failed states and the sustainability of the situation on the ground. I believe that Sierra Leone is an example of success, an intervention with minimal loss of life and ongoing post-conflict support. We should also remember that non-intervention has consequences. Syria is a case in point.

Jennifer Welsh (JW): There is always an obligation to assess whether intervention would do more harm than good, which leads to disagreement about what action, if any, is appropriate. With regard to Darfur, for example, very few people disagreed that there was a grave humanitarian crisis but many disagreed on whether military action would be able to address it.

DH: I think we are at risk here of parodying what critics of R2P say, namely that it is all about military intervention. In the first instance, R2P needs to be preventive. We must move on situations before gross abuses take place. This could be through diplomatic means, sanctions or preventive deployment of peacekeepers. One could say that the action in Mali was preventive – it saved a lot of lives. We ought to get better at acting early.

Q: How can we take action on atrocities when there is an ‘impasse’ at the UN Security Council? (Viv Williams)

JW: Disagreement amongst the five permanent members (P5) of the Council makes action difficult. But R2P is not owned by the Council. There are things that states can do individually to prevent atrocities, in terms of controlling the supply of weapons that fuel conflicts, for example. And when the Council is deadlocked, we can continue to pressure the P5 to uphold their responsibilities. There is also the option for the UN General Assembly, under its ‘Uniting for Peace’ resolution, to make recommendations on collective measures that can be taken.

DH: It is difficult to use R2P as it was intended if one of the P5 vetoes action. France has recently proposed that the P5 agree informally amongst themselves that they will not veto any resolution which seeks to deal with mass atrocities. I would like to see the UK supporting this proposal. I cannot imagine that this country would want to veto a resolution under such circumstances and we should say so.

Q: The international community failed to prevent mass atrocities in Sri Lanka in 2009. Considering the ongoing human rights situation, does R2P apply to Sri Lanka today? (Nirmanusam Balasundaram)

JW: The UN has engaged in an internal review following a report that concluded that there had been a systematic failure to protect the population in Sri Lanka. It was difficult to get the issue discussed at the Security Council – and this would remain the case today for similar situations – because its agenda is set by its members. However, the UN has created the ‘Rights Up Front’ initiative to address its own failings. This includes empowering those in the field to act. In 2009, UN actors in Sri Lanka were developmental and humanitarian – there was no political or peacekeeping force. As for Sri Lanka today, R2P is a preventive doctrine which encourages states to act before abuses occur, and there are a variety of states where there are risk factors.

Q: Should R2P be extended to cover all egregious violations of human rights? (Patricia Whisk) and, what is happening with regard to the school girls that have been abducted in Nigeria? (Fiona Barrie)

JW: The power of R2P is that it is understood narrowly and that it is meant to apply to the most exceptional, horrific acts on which there is widespread agreement.

DH: On Nigeria, I think the situation illustrates that countries are far too reluctant to ask for help. For a long time, the Nigerian government nurtured the illusion that they could deal with Boko Haram alone. Now, at last they have called for assistance although the girls sadly have not been found. Macedonia is the only country ever to have asked for preventive deployment of peacekeepers and it worked. Why don’t more countries ask for assistance sooner?

Q: China is set to take over from the US as the world’s leading nation. How will that affect the international community’s ability to respond to crises? (Audience, no name given)

MG: I think we are some years away from when China will have the global power projection of the US and the desire to play the role that America has in the last century. China still has modernisation and other internal issues to deal with. But it is worrying that there are growing tensions between China and its neighbours, particularly Japan.

DH: It is in periods like the present, where power relationships are changing very rapidly before our eyes, that there is a real risk of miscalculation and misjudgement. This is when we are most in need of the instruments of international law and the international institutions that we have set up since 1945. At the moment they are functioning partially but not completely. They need to be supported.

Q: I don’t think military intervention is ever the right approach. Shouldn’t we focus on prevention? (Clarissa Weinmann)

MG: Prevention is vital but I don’t agree that it should be our only focus. Sometimes we have to take more robust action once crimes have happened to prevent more violations and to stabilise the situation. The key is to make sure that we always think about the long-term consequences.

JW: Prevention is a popular thing to say but difficult to achieve. Governments need to invest – time and money – into preventive systems. They don’t do nearly enough, so ask your governments what they are doing to support prevention.